This fortnight’s big news was, of course, the successful rescue of 12 children and one adult stranded in a Thai cave by flooding, and there’s a surprise twist in the tale: the rescue was carried out using USB radio transceivers designed by a radio ham.

Hackaday explains that members of the British Cave Rescue Council (BCRC) called by the Thai authorities to assist with the rescue of 12 children and an adult stranded in the Tham Luang Nang Non cave had a now near-two-decade old device to assist them with communications: John Hey’s HeyPhone.

Designed for upper sideband (USB) communications at 87kHz, the HeyPhone’s low frequency allows it to penetrate deeper into the ground than more modern equipment when used with induction loop antennas or electrodes inserted into the ground – letting the rescuers stay in contact even as they dived and crawled along the cave’s passageways to reach their targets, who were all rescued safely. Sadly, one diver – Petty Officer Saman Gunan – lost his life setting up oxygen tanks to facilitate the rescue operation.

Buyers looking to pick up SDRplay, Airspy, or RTL-SDR software-defined radios via auction sites are being advised to keep their eyes peeled for unauthorised clones, being sold as though there were the original hardware

In a post on RTL-SDR, the clones are outlined as follows: SDRplay RSP1 clones being sold, inaccurately, as the improved RSP1A model with its additional filtering; the Airspy R2, sold without the usually-included metal enclosure; and the RTL-SDR V3, which “appear to just be standard RTL-SDRs without any real improvements apart from a TCXO” and which advertise features present in the V3 but not apparently implemented in the cloned design.

The same post highlights third-party HackRF boards being sold, but explains that the project’s open-source nature makes these simply a second-source supply – though buying direct supports creator Michael Ossmann.

Bob Van Valzah’s series on high-frequency trading via shortwave radio continues on the Sniper in Mahwah blog, with the latest post detailing site changes, the discovery of a new site, and “the connection between a sax-playing sheep farmer and shortwave trading.”

“If your business wants to set up a microwave link between two offices, the FCC has a category of licences just for you. If you want to be an AM, FM, or TV broadcaster, there’s obviously a category of licences for that,” Bob explains of the regulatory issues behind transatlantic high-frequency trading. “There are even licences for shortwave broadcasting to the general public. But what if your business wants to set up a private shortwave link between international offices? Sorry, there’s no permanent licence category for that. Nobody ever wanted such a licence until recently.

“FCC experimental licences seem to be the category of choice today. These allow experimental operation for a few years and may be renewed. Historically, experimental licences shared some constraints of amateur licences, specifically the old rules contained prohibition of commercial use and encryption. However, the rationale behind new rules issued in 2013 says they were ‘modernised,’ specifically to ‘keep pace with the speed of modern technological change.'”

The rest of Bob’s post can be found on Sniper in Mahwah, along with the first two entries in the series.

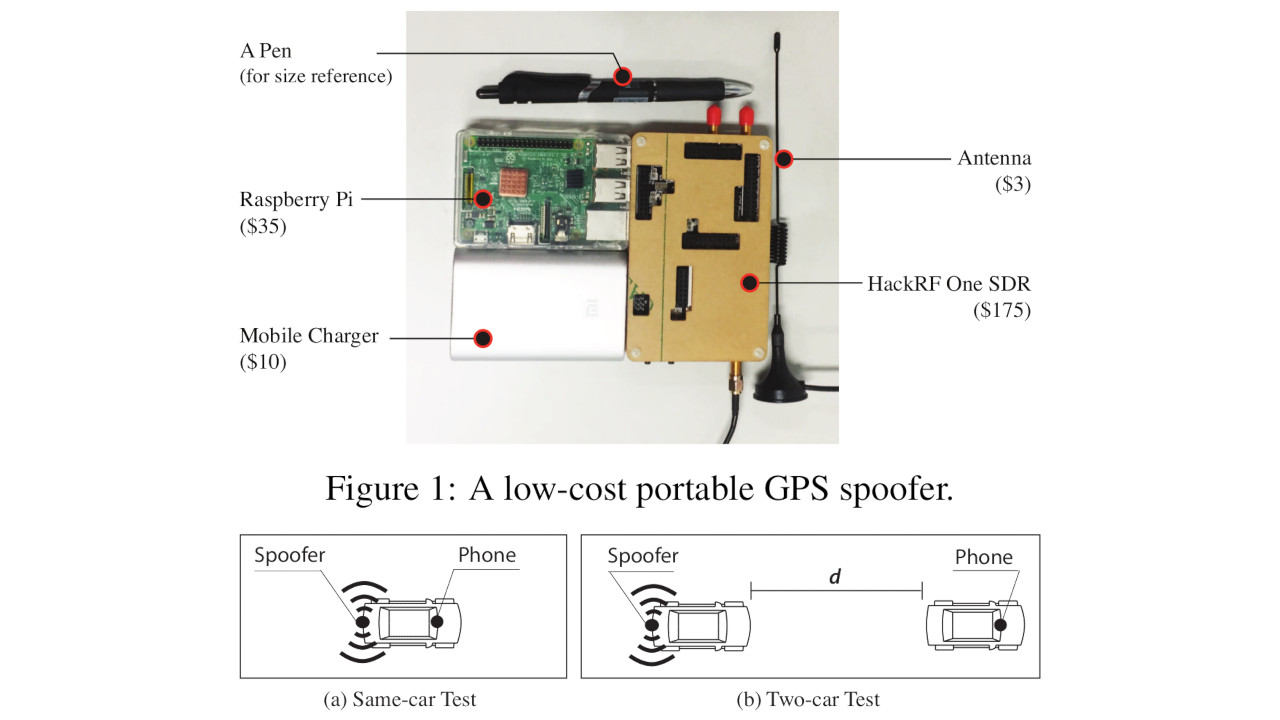

Researchers from Microsoft, Virginia Tech, and the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China have issued a paper which details the use of low-cost software-defined radio and single-board computer hardware to lure drivers relying on GPS-based navigation off their paths.

“In this paper, we explore the feasibility of a stealthy manipulation attack against road navigation systems,” the researchers write in introduction of the paper, All Your GPS Are Belong To Us: Towards Stealthy Manipulation of ROad Navigation Systems. “The goal is to trigger the fake turn-by-turn navigation to guide the victim to a wrong destination without being noticed. Our key idea is to slightly shift the GPS location so that the fake navigation route matches the shape of the actual roads and trigger physically possible instructions. To demonstrate the feasibility, we first perform controlled measurements by implementing a portable GPS spoofer and testing on real cars. Then, we design a searching algorithm to compute the GPS shift and the victim routes in real time.”

Using nothing more than a Raspberry Pi 3 single-board computer, HackRF open-source software defined radio, a whip antenna, and a battery pack, the team were able to redirect users in a driving simulator with a 95 percent success rate. Possible countermeasures for the attack discussed in the paper include upgrades to civilian GPS to use encryption, dedicated and trustable ground infrastructure, the use of additional navigation signals like GLONASS and Galileo, Wi-Fi base station location mapping, dead reckoning via an internal inertial management unit (IMU), and even computer vision based location detection.

The full paper is available via Virginia Tech (PDF warning).

South Korea has indicated it plans to launch commercial 5G New Radio networks by March next year, ahead of other countries’ plans to send the next-generation networks live for commercial users some time in 2020.

According to the Korea JoongAng Daily, the three largest mobile operators in South Korea – SK Telecom, KT, and LG U+ – have jointly agreed to launch their commercial 5G networks on “5G Day” in March 2019. This will, supposedly, be a true launch ready for commercial users, rather than the small-scale field trials we’ve seen before.

For developing nations, though, there’s a barrier to entry: the high price of radio frequency spectrum licences, a report from the GSM Association has concluded.

“To deliver affordable, widespread and high-quality mobile broadband services, mobile operators require affordable and predictable access to sufficient radio spectrum. Well-designed spectrum policy is therefore a critical input for a thriving digital economy,” the GSMA explains in its latest intelligence report. “The right spectrum pricing policies can help enhance consumer and social welfare in developing countries. Policies that seek to maximise state revenues, however, can have a negative influence on consumer outcomes, including more expensive mobile services and reduced network investment.”

Concluding that “high spectrum prices are a significant issue in developing countries [and] final spectrum prices in developing markets were more than three times those of developed countries once income levels are taken into account,” the GSMA suggested that “it is crucial that spectrum policies in developing countries support fast and sustainable development of the mobile sector.”

The full report is available from GSMA Intelligence (PDF warning).