Wavelet Lab, creator of the uSDR software-defined radio module, is preparing to launch crowdfunding campaigns for two new modules built around Lime Microsystems’ LMS7002M: the compact xSDR and wider-range sSDR.

“xSDR is a compact, single-sided M.2 software-defined radio designed for seamless integration into modern computing platforms,” says Wavelet Lab’s Andrew Avtushenko of the first of the new modules. “The ‘x’ stands for ‘extended’ – xSDR delivers extended bandwidth in the same minimal footprint as our previous model, uSDR. With 2×2 MIMO [Multiple-Input Multiple-Output] RX/TX [Receive/Transmit] channels, a wide 30MHz-3.8GHz tuning range, and up to 122.88 MSPS [Mega-Samples Per Second] sampling, xSDR is a flexible platform for embedded RF, wireless research, signal intelligence, and rapid prototyping.”

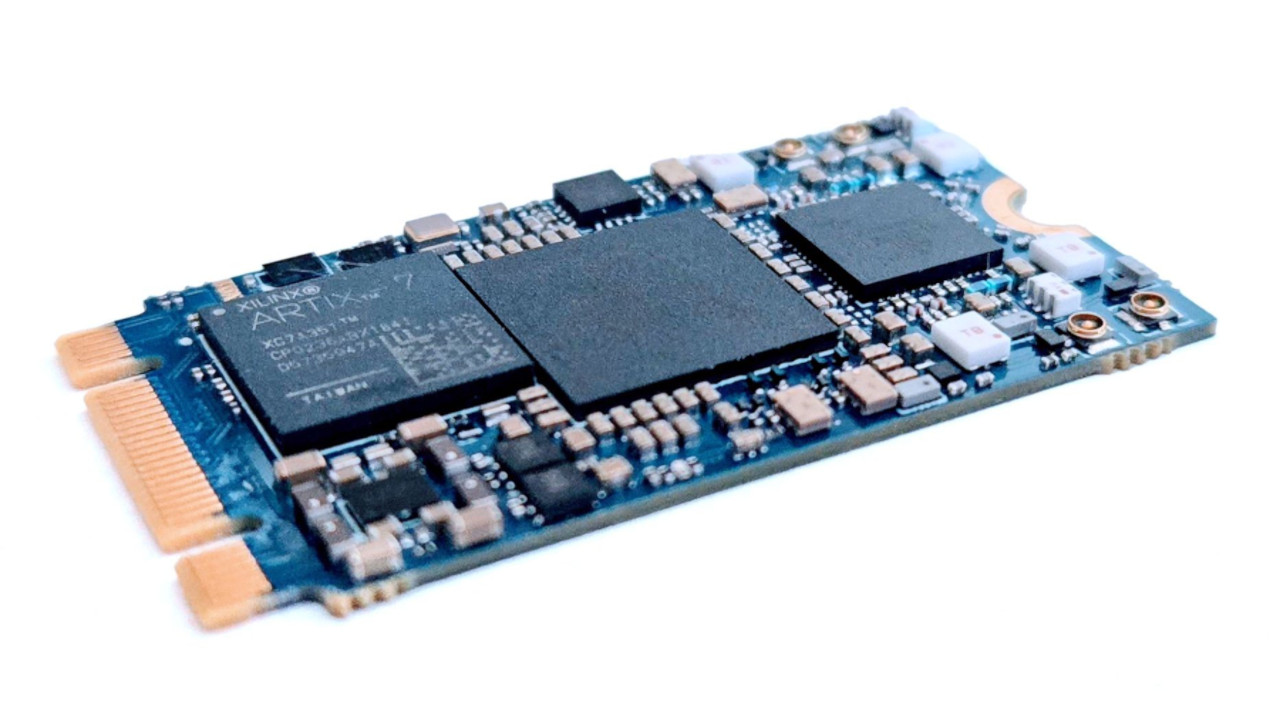

The xSDR is built around the Lime Micro LMS7002M, the same field-programmable radio-frequency chip at the heart of the LimeSDR family, and an AMD Artix-7 XC7A35T field-programmable gate array (FPGA). For those who need a wider frequency range, Wavelet Lab has also announced the sSDR – described by Andrew as “a cutting-edge high-performance M.2 software-defined radio card [which] features 2 RX/TX channels and an RF range spanning from 30MHz to 11GHz” thanks to the addition of a Lime Micro LMS8001 up/down converter.

Both boards are designed to share the same permissively-licensed codebase as the original uSDR module, and fit in the same M.2 slot on a host device – making for an easy upgrade path, Andrew says. Gateware for both devices is being made available under the permissive variant of the CERN Open Hardware Licence 2.

More information is available on the xSDR and sSDR Crowd Supply pages, where interested parties can sign up to be notified when the campaigns open for funding.

Artist Théo “Rootkid” Champion has turned a Raspberry Pi and a software-defined radio in to a wall light that visualises Bluetooth and Wi-Fi signals in real-time: the Spectrum Slit.

“Spectrum Slit is a sculptural installation that renders visible the otherwise imperceptible electromagnetic activity that permeates contemporary interior spaces,” Théo says of the project. “While a room may appear visually calm and silent, it is continuously traversed by dense fields of radio-frequency transmissions generated by wireless communication technologies. This work exposes that hidden layer of reality by translating radio wave activity into light (and sound) in real time.

“The installation measures radio signals primarily within the 2.4GHz and 5GHz bands frequencies used by Wi‑Fi, Bluetooth, and other domestic wireless devices. Using a software-defined radio, the piece continuously scans these ranges, sampling signal strength across the spectrum. This data is processed live and mapped onto a linear array of 64 luminous filaments arranged along a U-shaped steel structure, visually echoing scientific frequency plots. Each filament corresponds to a specific segment of the measured spectrum, its brightness directly driven by local electromagnetic intensity.

“The resulting display is dynamic and situational,” Théo says. “At moments of low network usage, the sculpture emits faint, intermittent light, reflecting the ambient background noise of an urban environment. As wireless activity increases – through web browsing, video streaming, messaging, or connected devices – the filaments surge and saturate, forming dense bands of intense illumination. The sculpture thus becomes a temporal portrait of collective digital behaviour, shaped by the rhythms of daily life.”

More information is available on Théo’s website, with a video build log available on YouTube.

Engineer Aleksa Bjelogrlic has announced a milestone in the ThunderScope open-source oscilloscope project: the final hardware revision and submission for mass production.

“The ThunderScope design is done,” Aleksa writes on Mastodon. It’s out for quotation. The hard part is over. That one zip file represents the culmination of almost 7 years of work. I need a break… and a stiff drink.”

The ThunderScope opened for crowdfunding in September 2024, promising a “re-imagining of how test equipment is designed and used” by splitting the usual design into a “no-compromises analog frontend” which connects to the user’s computer for processing over high-speed interfaces — allowing for a considerably more compact design, and allowing its capabilities to improve as both software and hardware on which it’s running are upgraded.

Since closing crowdfunding in November 2024, Aleksa has been working on getting the hardware and software, Andrew Zonenberg’s ngoscopeclient, ready for mass production and deployment — and now that process is finally complete. The next step: gathering quotations for production and putting the machines to work building people’s ThunderScopes.

More information is available on Crowd Supply, while the ThunderScope gateware, hardware, and software are made available on GitHub under the permissive MIT licence.

Daniel Estévez has released tooling, written from scratch in Rust, designed for those interacting with spacecraft using the Cubesat Space Protocol.

“CSP is the Cubesat Space Protocol. It is a network protocol that was developed by Aalborg university, and is commonly used in cubesats, in particular those using GOMspace hardware,” Daniel explains. “Initially the protocol allowed different nodes on a satellite to exchange packets over a CAN bus, but eventually it grew into a protocol that spans a network composed by nodes in the satellite and the groundstation that communicate over different physical layers, including RF links.

“Recently I have been working on a project that involves CSP. To measure network performance and debug network issues, I have written some tooling in Rust, as well as a Wireshark dissector in Lua. The Rust tooling is an implementation from scratch and doesn’t use libcsp. Now I have open sourced these tools in a csp-tools repository and csp-tools Rust crate.”

The tools Daniel has released are: cspdump, a CSP-specific equivalent to tcpdump, capturing CSP packets and writing them to a file; csp-iperf, a performance-measuring tool which sends CSP packets to a ping service and measures throughput, round-trip timing, and packet loss; and csp-ping-server, the other half of csp-iperf. All tools support CAN and ZMQ PUB/SUB interfaces.

More details are available on Daniel’s blog, while the tools themselves are available dual-licensed under the user’s choice of the permissive Apache Licence 2.0 or MIT licence on GitHub. The tools are also available as a Rust crate crates.io.

Daniel has also recorded a full Narrowband-Internet of Things (NB-IoT) conversation from the startup of a V16 beacon – now mandatory as a replacement for traffic warning triangles in Spain.

“In my previous post I decoded a transmission from a V16 beacon,” Daniel explains. “The V16 beacon has mandatorily replaced warning triangles in Spain in 2026. It is a device that contains a strobe light and an NB-IoT modem that sends its GNSS geolocation using the cellular network. It is said that the beacon first transmits is geolocation 100 seconds after it has been powered on, and then it transmits it again every 100 seconds.

“In that post I recorded one of those transmissions done after the beacon had been powered on for a few minutes and I decoded it by hand. I showed that the transmission contains a control plane service request NAS message that embeds a 158 byte encrypted message, which is what presumably contains the geolocation and other beacon data.

“In that post I couldn’t show how the beacon connects to the cellular network and sets up the EPS security context used to encrypt the message, since that would have happened some minutes before I made the recording. I have now made a recording that contains both the NB-IoT uplink and the corresponding NB-IoT downlink and starts before the V16 beacon is switched on.”

The full analysis is available on Daniel’s blog, while the recording is available on Zenodo under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

S. “mulymule” Rayworth has designed a 3D-printable aim-assist system for satellite tracking, built around LILYGO’s T-Display S3 development board: the SatTrack.

“While using a satellite-tracking app on my phone, I had the idea to create a stand-alone ESP32-based satellite tracker that provides both satellite information and a POV (point-of-view) aiming display, allowing you to manually aim the antenna during a satellite pass,” Rayworth explains of the project.

“The result is SatTrack – a compact handheld device that can be mounted directly to an antenna and used to visually track satellites in real time. It can also be used independently for general satellite tracking, such as monitoring ISS passes when conditions are right.

The included mount allows the tracker to be attached directly to the antenna and secured using a simple cable/zip tie, keeping everything lightweight and portable. SatTrack supports up to 20 configurable satellites, which can be managed via a built-in web portal once the device is connected to Wi-Fi. You can also set or update your geographic location through the portal. The device offers four different display modes to suit different tracking needs: 2D map; 3D map + next pass info; next passes; POV live aim view.”

The 3D-print files and firmware for the project are available on Printables under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence.

Developer Jimmy Fitzpatrick has announced the third major release of Spectre, an open-source tool for recording radio signals and spectrograms from a wide variety of software-defined radio hardware – lightweight enough to run well on a Raspberry Pi single-board computer.

“Spectre is a free and open source SDR-agnostic program for recording radio signals and spectrograms,” Jimmy writes of the tool. “It’s geared for hobbyists, citizen scientists, and academics who want to achieve scientifically interesting results at low cost. Powered by GNU Radio and FFTW, it provides high performance on modest hardware. Applications include: solar and Jovian radio observations; educational outreach and citizen science; amateur radio experimentation; lightning and atmospheric event detection; RFI monitoring.

“After a good few months of labour, we’re excited to release v3 of Spectre. Notably (to name a few things): I/Q sample recordings are now compatible with Inspectrum and can be read easily with NumPy; I/Q sample recording types are now configurable (e.g., fc32 for complex 32-bit floats or sc8 for complex 8-bit signed integers); [you can] record I/Q samples and spectrograms at the same time; [you can] record data from multiple SDRs at the same time.”

Full release notes are available on GitHub, along with the project’s source code under the reciprocal GNU General Public Licence 3.

Software engineer Anthony Templeton has been working on improving the performance of his astronomical and spacecraft toolkit astroz — hitting the point where it can calcualte 326 million satellite propagations per second, running entirely on a standard CPU.

“I’ve spent the past month optimizing SGP4 propagation and ended up with something interesting: astroz is now the fastest general purpose SGP4 implementation I’m aware of, hitting 11-13M propagations per second in native Zig and ~7M/s through Python with just pip install astroz,” Anthony writes. “I’ve since added multithreading and pushed astroz to 326M propagations/sec.

“SGP4 is the standard algorithm for predicting satellite positions from TLE [Two-Line Element] data. It’s been around since the ’80s and most implementations are straightforward ports of the original reference code. They work fine. But ‘fine’ starts to feel slow when you need dense time resolution. Generating a week of ephemeris data at one-second intervals is over 600,000 propagations per satellite. Pass prediction over a ground station network needs dense propagation around visibility windows to pinpoint exact rise and set times. Conjunction screening wants fine-grained time steps across orbital periods to avoid missing close approaches between coarse samples.”

Anthony’s work provides the kind of throughput required for rapid calculations of multiple satellites, scaling according to the number of cores available in the system’s CPU. Even running on a single core, it’s 11 times faster than the standard python-sgp4 implementation and nearly twice as fast as a Rust sgp4 implementation; when scaled to 16 threads on an AMD Ryzen 7 7840U mobile processor it can reach over 300 million propagations per second.

The tricks behind the performance gains are detailed in Anthony’s original and follow-up blog posts, while the source code for astroz is available on GitHub under the reciprocal GNU General Public License 3.

Finally, the anonymous creator behind the Nostalgia For Simplicity YouTube channel sent a single-node Advanced Mobile Phone System (AMPS) network live — to understand how his uncle pulled off a trick decades prior.

“When I was a kid, I watched my uncle do something I did not understand,” the video explains. “He would type a code into his phone and suddenly he could hear someone else’s call. Back then, I didn’t even know what was really going on. But that moment got stuck in my head. I have kept this code in my memory for 22 years because I wanted to understand what it actually did.”

To find out, the YouTuber put together a simple low-power single-node AMPS network, designed to connect to an Ericsson DH668 mobile phone. “AMPS was analog,” the creator explains. “The cell site slices the radio spectrum into hundreds of numbered channels. Each call lives on one of those channels. Back in a real city, lots of channels would be busy at the same time. If you tune the right one, you would land on someone else’s conversation. What he did wasn’t right, but it shows the weakness of 1G and why the world moved on from it.”

The full video is available on the Nostalgia for Simplicity YouTube channel.